To read the initial entry in the State-By-State series, click here.

The first entry in the State-By-State series is relatively easy, given that Robert Pasquill, Jr. did a state-specific study in 2008. Pasquill’s The Civilian Conservation Corps in Alabama, 1933-1942: A Great and Lasting Good is an asset for its appendices alone. Add in the fact that the book includes a disk of interviews with CCC enrollees and you’ve got an irresistible package for CCC buffs or anyone seeking information on Alabama CCC projects.

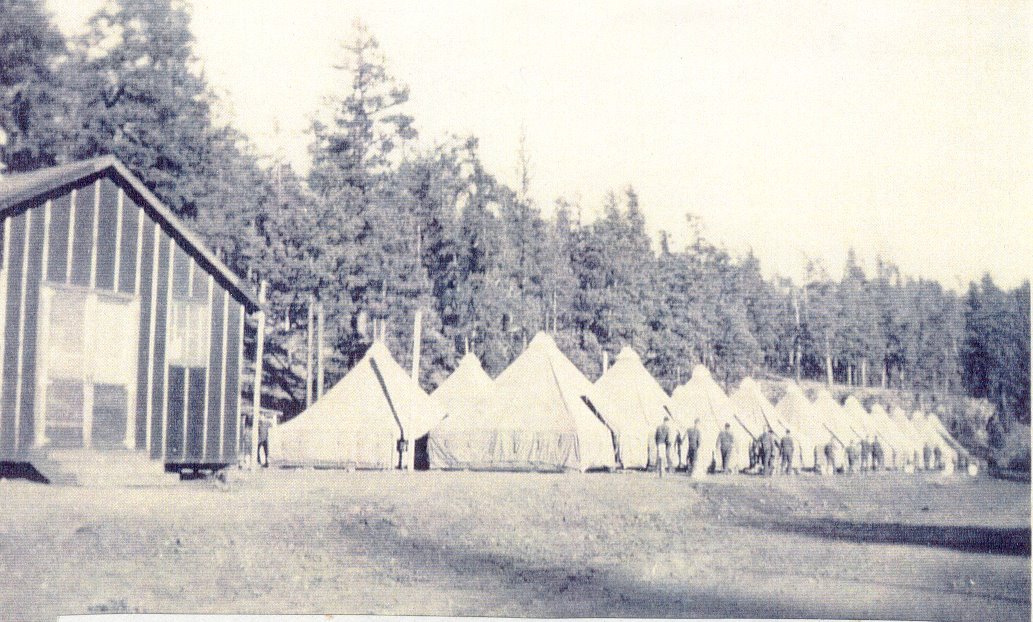

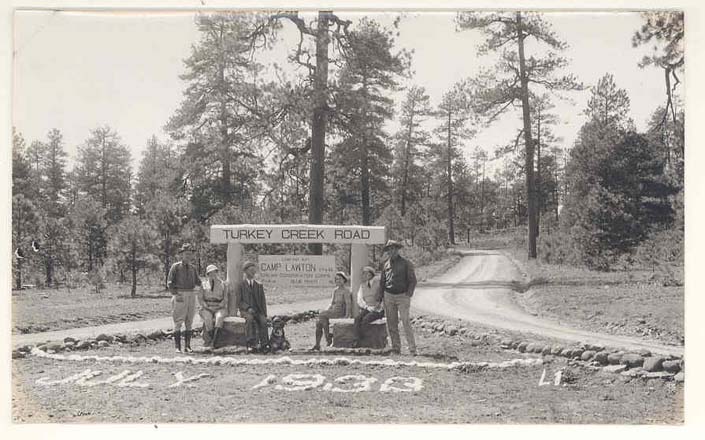

According to statistics cited by Merrill in Roosevelt’s Forest Army, the CCC in Alabama strung more than 1,800 miles of telephone lines, built over 3,000 miles of roads and truck trails, planted just over 60,000 trees and built 659 bridges of various types. Merrill reports that in 1937 the aggregate number of Alabama men employed by the CCC was 66,837 and that an estimated $16.4 million in allotments was made to dependents by enrollees.

Not surprisingly, Pasquill cites Merrill’s work in his summary of CCC accomplishments in Alabama. Pasquill also quotes at length from an article that ran in the July 16, 1942 edition of the Moulton Advertiser, just a couple weeks after the CCC was officially disbanded. I won’t run the entire entry here, but will pass along this small bit from the article, entitled “A Great and Lasting Good Accomplished by the CCC”:

[During the lifetime of the CCC] “CCC camps under the jurisdiction of the U.S. Forest Service and State Forester advanced the cause of forest conservation in Alabama by at least a generation both in the national forests and on state and privately owned land.”

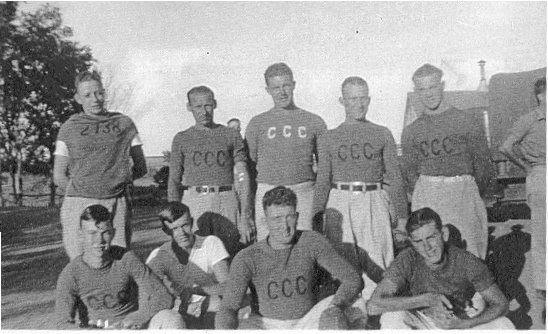

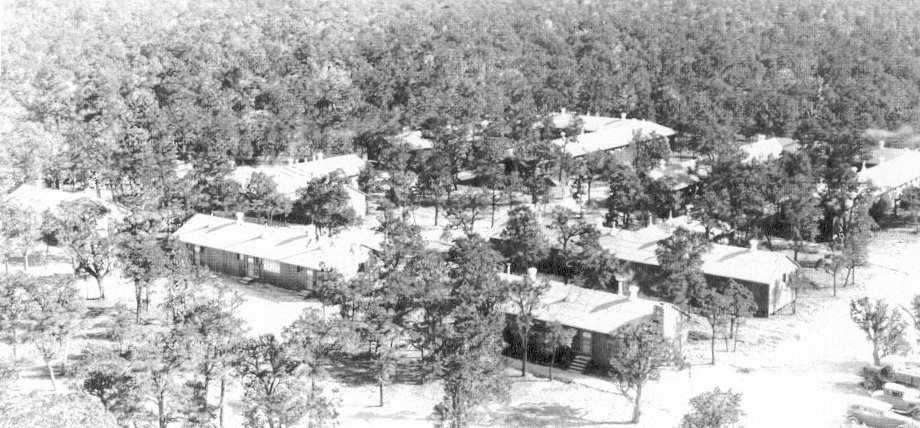

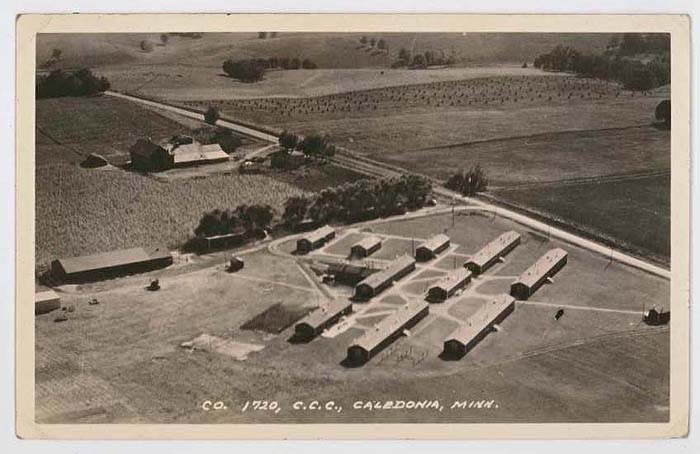

As we’ll see with every state, Alabama’s CCC camps were like small towns and many camps had camp newspapers that sported names like Bull Thrower, Camp Jester, Mess Kit and See See See. Pasquill’s book includes a helpful list of camp newspapers in the appendices.

As we’ll see with every state, Alabama’s CCC camps were like small towns and many camps had camp newspapers that sported names like Bull Thrower, Camp Jester, Mess Kit and See See See. Pasquill’s book includes a helpful list of camp newspapers in the appendices.Pasquill’s list of Alabama CCC camps breaks them out under technical services: U.S. Forest Service, Soil Conservation Service, Tennessee Valley Authority, State Parks, Private Forest Projects and State Forest Projects. Additionally, while Alabama hosted a number of colored CCC companies and even some CCC companies comprised of black World War I veterans, Pasquill’s text isn’t particularly user-friendly for researchers looking for specific references to all-black CCC camps or CCC companies; there are no index listings to direct the reader to topics related to “race,” or “racism” or ‘African-American enrollees,” for example. On the other hand, a diligent reader or researcher will be able to cross-reference the camp listing against the individual camp histories to get an idea of where the all-black CCC companies worked in Alabama.

One could argue that the CCC’s only true failing was in the area of racial integration and equality; indeed the incidence of racism in the selection, enrollment and deployment of minority groups, especially blacks and seemingly especially in the southern states, is the one sad aspect of the CCC program that we’ll encounter consistently as we progress through this state-by-state history. Though the legislation that created the Civilian Conservation Corps included language prohibiting discrimination based on race, problems cropped up almost immediately during the initial selection process in the individual states. For an excellent account of these initial problems and indeed a valuable discussion of the problem of racism in the CCC, see John Salmond’s groundbreaking work from the 1960s, The Civilian Conservation Corps, 1933-1942: A New Deal Case Study. Of particular interest with respect to racial policy in the CCC is Salmond’s discussion in Chapter 5, “The Selection of Negroes, 1933-1937” (A copy of Salmond’s important work is now available online and can be viewed here.)

So, despite this very minor shortcoming, let there be no doubt that if you’re looking for information on the CCC in Alabama, Robert Pasquill’s book is where you need to start and it may indeed contain everything you need, but in the event you’re still looking, here are some links to other sites with information on the CCC in Alabama:

Click here for a history of CCC work in Dekalb County, Alabama.

For a look at the U.S. Forest Service history of CCC work in Region 8, which included Alabama, click here.

Image Credits: State Map is an edited detail from Cohen's The Tree Army. The photo is also from Cohen and is a view of the recreation room of Camp P-60, home to Veteran's Company 2420, Chatom, Alabama.

Next stop on the State-By-State tour: (The Territory of) Alaska.

No comments:

Post a Comment