With our elected officials frequently deadlocked over seemingly petty squabbles that prevent meaningful legislation from being passed, it seems astonishing that the legislation creating the Civilian Conservation Corps sailed through congress in less than three weeks. The seeds of a work relief program with a focus on conservation of both young lives and natural resources were alive in Franklin Roosevelt's mind years before his inauguration as president. Indeed the following timeline outlining the first significant events leading up to the creation of the CCC on March 31, 1933 dates back as early as 1910. For an outstanding account of not only the creation of the CCC but numerous aspects of its operation between 1933 and 1942, see John Salmond's book The Civilian Conservation Corps 1933-1942: A New Deal Case Study. In the meantime, here's a quick thumbnail sketch of the birth of the Civilian Conservation Corps.

1910

Franklin Delano Roosevelt takes over the family estate at Hyde Park and immediately begins a reforestation effort.

1931

Roosevelt sponsors an amendment to the New York constitution giving the state government authority to acquire and reforest marginal lands with funds created from the sale of bonds.

1932

Roosevelt adapts a reforestation program for use in unemployment relief.

July 2

In accepting the Democratic presidential nomination, Roosevelt proclaims that he has, “a very definite program for providing employment…,” through the establishment of a conservation program.

1933

January

James Couzens, a Republican senator from Michigan fails in his attempt to pass a Senate bill authorizing the use of the Army for unemployment relief. Though a failed effort, Couzens’ measure introduces the concept of military involvement in relief efforts.

March 9

Meeting with advisors, including the Secretaries of the interior, agriculture, and war FDR diagrams his plan to put 500,000 men to work on conservation-related projects. He asks them to prepare draft legislation, requesting they complete the task by days end. Roosevelt is given a draft document at 9 that evening and further discussion is conducted immediately.

March 14

Roosevelt sends a memorandum to the secretaries of war, interior, labor and agriculture, asking them to form “an informal committee of the Cabinet to co-ordinate the plans for the proposed Civilian Conservation Corps.”

March 15

At his third press conference since being inaugurated president, Roosevelt expounds on the proposed forestry work program, including the proposed wage of $1 a day. Roosevelt explains that swift action on the matter is a foregone conclusion.

March 21

Roosevelt’s message concerning the “Relief of Unemployment” is sent to the Congress. In this message Roosevelt outlined a three-pronged attack on the problem, with the first effort being, “the enrollment of workers now by the Federal Government for such public employment as can be quickly started and will not interfere with the demand for, or the proper standards of, normal employment.”

More specifically, Roosevelt uttered what may be the most often quoted phrase in connection with the Civilian Conservation Corps:

I propose to create a Civilian Conservation Corps to be used in simple work, not interfering with normal employment and confining itself to forestry, the prevention of soil erosion, flood control and similar projects. I estimate that 250,000 men can be given temporary employment by early summer if you give me authority to proceed within two weeks.

Roosevelt went on to state:

More important will be the moral and spiritual value of such work. The overwhelming majority of unemployed Americans who are walking the streets and receiving private or public relief would infinitely prefer to work. We can take a vast army of these unemployed out into healthful surroundings.

Following the President’s message at bill entitled “The Relief of Unemployment Through the Performance of Useful Public Work and for other Purposes” was introduced into both the Senate and the House.

Labor leaders quickly condemn the plan for its wage and recruitment provisions and because of the involvement of the Army.

March 22

Roosevelt calls members of the Senate Committee on Education and Labor, and the House Committee on Labor to the White House where he explains his CCC plan in more detail and attempts to allay the fears expressed by organized labor and members of the Socialist party.

March 23-24

Joint Senate and House hearings begin in an atmosphere of cooperation possibly due to Roosevelt’s evening meeting at the White House the night before. Presiding over the hearings is Senator David I. Walsh, a Massachusetts Democrat and chairman of the Senate Committee on Education and Labor. Walsh prods the proceedings forward in an effort to adhere to Roosevelt’s stated desire.

Among those testifying at the Joint hearing is Chief forester Major Stuart who testified at length regarding the need for forest workers. Stuart also makes a successful bid to broaden the program’s scope of work to include not just national forests but also state and private forests. Without such a change, Stuart argues, there will have to be a transfer of men from east of the Mississippi River to the Rocky Mountain region where 95 percent of the public domain is situated. (With 70 percent of the unemployment located east of the Mississippi, it didn’t make sense to transport men westward to give them work.)

Secretary of Labor, Miss Frances Perkins also stresses the programs aim of work relief when questioned about the proposed $1 a day wage for enrollees. She explains that most of the workers are expected to be young, single men and that the CCC should not be viewed “in the sense of providing real wage-producing employment.”

Army chief of staff, General Douglas MacArthur testifies that there will be “no military training whatsoever,” with the military restricting its participation to gathering the men selected by the Department of Labor, outfitting the men, giving the men a physical examination and physical conditioning before transporting them to their camps where they would be turned over to the Department of Agriculture.

The next witness is William Green, president of the American Federation of Labor. Green attacks the program on three points: regimentation of labor, low wages and funding. To Green the mandatory allotment and the involvement of the military “smacked of fascism, Hitlerism, of a form of Sovietism…” Green argues that the CCC wage of $1 a day would establish that as the national wage for workers. Other labor representatives also testify and the hearing adjourns on a far less optimistic note than it convened.

March 27

An amended S. 598 is reintroduced into the Senate. In response to the objections raised by labor, it was agreed that the focus should be on the two aspects of the program for which there were no objections from any side: the chance to perform forestry work as a means of relieving unemployment and the use of unobligated funds to pay for the program. The re-submitted bill merely authorized the President to work in the public domain, perform reforestation and employ unemployed citizens to perform the work.

In the House opposition to the bill is more robust and broad based. Despite indications from labor leaders that the $30 monthly wage would not be contested, an effort was launched to set the pay scale at $50 a month for single enrollees and $80 a month for married enrollees.

March 28

The senate bill is passed by voice vote over dwindling opposition, with minor amendments and in part because of the continuing efforts of Senator Walsh.

March 29

The House considers the bill amended and passed by the Senate on March 28th. Representative Connery stood to protest the proposed wage and dramatically announced that once again, labor leaders had again changed their position and now opposed the bill. Still another faction stood to argue that the measure imparted nearly dictatorial powers on the president and would lead a majority of the population believing that “it is the Government’s duty to put them on the pay roll.”

Nevertheless, the intent of the bill receives wide support in the House, with many recognizing it as focusing on relief of unemployment, not wage control. Representative Thomas G. Cochran of Missouri, stated that he disliked many of Roosevelt’s proposals, but admitting that “…I do like the way the President of the U.S. is trying to meet this emergency…”

Like Senator Walsh in the senate, Representative Robert Ramspeck, a Democrat from Georgia, carries the torch for the bill in the House, emphasizing the emergency nature of the legislation and its important relief function.

Connery’s proposal to set the monthly wage at $50 fails, along with a last minute effort by Republicans to delay proceedings on a point of order. Only three amendments are adopted, including that proposed by Representative Oscar De Priest, a Republican from Illinois and the sole African-American Congressman. De Priest proposed “that no discrimination shall be made on account of race, color, or creed…under the provisions of this Act.”

The bill is passed by a voice vote.

March 30

The Senate accepts the House amendments to the bill and it is forwarded to the President.

March 31

President Roosevelt signs into law the legislation creating the Emergency Conservation Work (ECW) program.

April 17

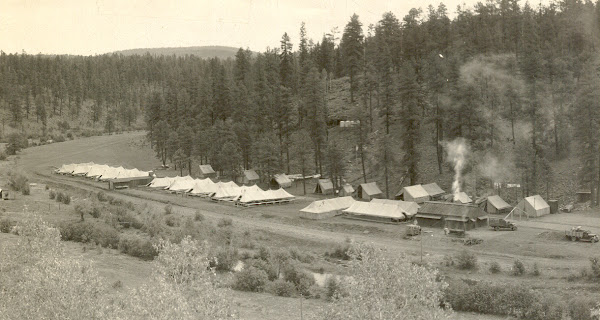

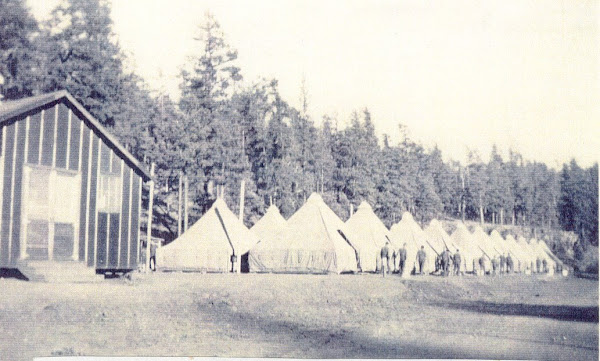

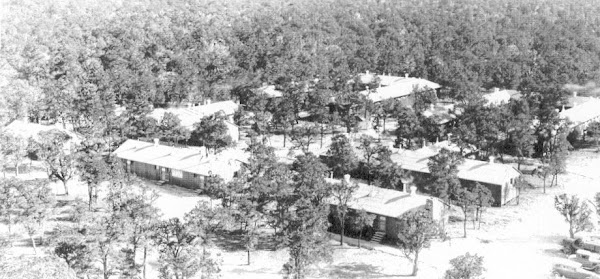

First CCC camp is established in the George Washington National Forest in Virginia.

In an article titled “Rizzo Goes To Work,” Time magazine reports that a week earlier, 19 year old Fiore Rizzo reported to the Army Building in downtown Manhattan and reported for duty as the first CCC enrollee.

We couldn’t have asked for better weather or a more enthusiastic group in attendance to celebrate the dedication of Arizona’s first CCC Worker Statue on October 25, 2008.

We couldn’t have asked for better weather or a more enthusiastic group in attendance to celebrate the dedication of Arizona’s first CCC Worker Statue on October 25, 2008. Following remarks by guest speakers, Arizona’s first CCC Worker Statue was unveiled by Gerald Johnson, CCC veteran and Colossal Cave Mountain Park Director Martie Maierhauser. It was Gerald Johnson’s generous initial donation in 2004 that got Arizona’s statue campaign rolling and ultimately, an additional donation from Mr. Johnson insured that the statue would be a reality. It is safe to say that without Gerald Johnson, the statue dedication would not have taken place in this, the 75th anniversary year of the CCC.

Following remarks by guest speakers, Arizona’s first CCC Worker Statue was unveiled by Gerald Johnson, CCC veteran and Colossal Cave Mountain Park Director Martie Maierhauser. It was Gerald Johnson’s generous initial donation in 2004 that got Arizona’s statue campaign rolling and ultimately, an additional donation from Mr. Johnson insured that the statue would be a reality. It is safe to say that without Gerald Johnson, the statue dedication would not have taken place in this, the 75th anniversary year of the CCC.