Will we understand the

value of our history only after we have lost it?

In addition to helping

folks find information about the Civilian Conservation Corps, another critical

component to this thing we call CCC “resources” is the preservation of endangered

items and bits of information. Clearly a

resource is of no use if it’s wasted, lost, destroyed or hidden away so deep in

an archive vault that the average person cannot access it.

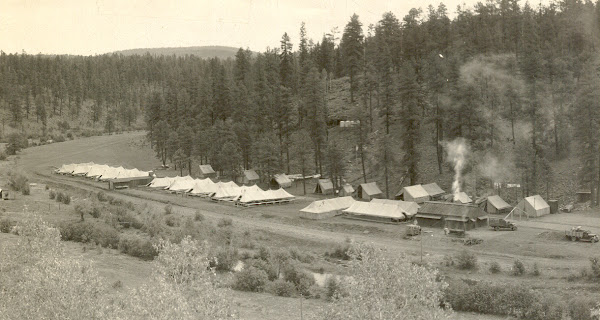

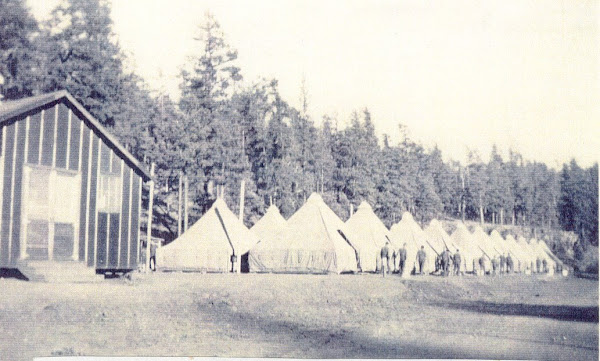

I was recently contacted

by the folks at Appalshop Archive in Whitesburg, Kentucky. It seems there is silent film footage shot at

Camp SP-10-K near Pineville, Kentucky in 1938 that is in need of

preservation. For the sake of getting

the word out quickly, I’ve pulled a quote directly from their fundraising site:

“In 2008 the Appalshop

Archive received the donation of a 1938 16mm silent b/w film documenting the

CCC camp in Pine Mountain State Park near the coal mining community of

Pineville, KY. It was made by Park

superintendent and CCC supervisor Carl Zody.

Camp SP-10 men are seen constructing roads and bridges, operating

vehicles, and cutting native sandstone for the Laurel Cove amphitheater (which

is still a local landmark central to the town’s annual Kentucky Mountain Laurel

Festival). The at-risk film is the most

extensive known moving image materials of CCC activity in Pineville. It is also unique in that it was made by a

Park employee rather than by the U.S. Department of the Interior, whose films

were intended to promote the program to the public.”

I think the critical

thing to consider in this case is that the effort is to raise funds in order to

preserve and exhibit this rare piece

of film history. Preservation of CCC history will insure that items are kept safe

but possibly never seen. Exhibition of CCC history brings the CCC

story to thousands but risks damage to the items being exhibited. The folks at Appalshop Archive are working to

do both and they need the public’s help to make that happen.

Again, because Appalshop

is working to meet a fundraising deadline, I’ve chosen to pull the contact

information directly from their website in order to get this piece posted as

soon as possible. Here is how you can

help:

“To donate by credit card

go to the Contribute Now button at the top right of this page (http://www.indiegogo.com/projects/appalachia-coal-camps-home-movies-and-the-ccc?c=activity). If you would prefer to make your

tax-deductible contribution by check, just make it payable to APPALSHOP, INC.

and mail to: Appalshop Archive, 91 Madison Ave, Whitesburg, KY, 41858.”

There are premiums

offered based on the level of contribution you make – call it a “perk” or an

incentive – but there is also a deadline for the current fundraising effort. To view the fundraising web page and to see

the range of incentives being offered, visit the website here (scroll down the

page to view the section on the Pineville CCC film): http://www.indiegogo.com/projects/appalachia-coal-camps-home-movies-and-the-ccc?c=activity

Think of it this way: Somewhere, there are people searching for

information about a family member or a loved one who worked in a CCC camp in

Kentucky. Wouldn’t you feel great if you

knew that you’d helped make it easier for those folks to perhaps catch a

glimpse of their CCC boy on film? That

should be incentive enough.

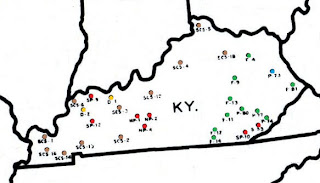

For a history of the CCC in

Kentucky, see Connie M. Huddleston’s book Kentucky’s

Civilian Conservation Corps, 2009, The History Press.

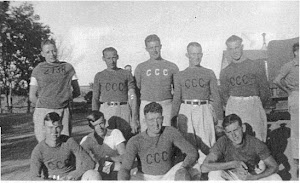

(Header illustration:

Edited detail from the CCC Company photo, Camden, Maine. Courtesy of John McLeod.)