Georgia was situated in the 4th Corps area along with North Carolina, South Carolina, Florida, Alabama, Tennessee, Mississippi and Louisiana. The 4th Corps area was commanded by Major General George Van Horn Moseley, who wrote of the CCC: “Though I feel that all of the participating Federal departments – Agriculture, Interior, Labor, and War – have done a fine job, the credit for the wonderful reputation achieved by the Civilian Conservation Corps must go primarily to the lads themselves. I have never seen a finer group of young men. They have met their part of the bargain just one hundred percent, and they have reaped a just reward.” (Moseley's comments appeared as a preface to a 1935 District "E" Annual. It should be noted that Moseley's high opinion of CCC enrollees may not have extended to all enrollees. Salmond refers to him as a "quasi-fascist" and by inference we can assume he may not have been highly in favor of the recruitment of black enrollees into the CCC.)

The Federal Security Agency

Annual Report of the Director of the Civilian Conservation Corps for fiscal year 1942 includes the following detailed reference to CCC work in Georgia on page 48 under the heading Southern Region – Atlanta, Georgia. The entry states:

“Largely through the fire control improvements and facilities constructed by the CCC, it has been possible for the State Foresters in the Southern Region to provide fire control for millions of acres of privately owned timber lands that otherwise would have continued to suffer severe damage annually. At the beginning of the CCC program in 1933 there were about 47 million acres in the South receiving fire protection. By January 1, 1942, this had increased to 75 million acres.”

No doubt, Georgia garnered its share of important forest protection improvements in the southern United States as well as other valuable work by the creation of the CCC in 1933. Perry Merrill breaks out some of the work totals in his book

Roosevelt’s Forest Army. For example, in Georgia, between 1933 and 1942, the CCC strung 3,638 miles of telephone lines, build 425,829 check dams and erosion control features, planted over 22 million trees and spent over 153,000 man-days fighting forest fires. Dependents living in Georgia received over $19 million in allotments from enrollees during that time!

As for the aforementioned forest protection work, the CCC erected 500-watt radio transmitters at two sites to improve communication between fire towers and fire crews. Additionally, the CCC built facilities at Timber Protective Organization sites established as part of a state program.

Merrill notes that the average number of CCC camps to operate in Georgia was 35 and we can compare this average against camp totals for 1937 and 1939. According to the

1937 Annual Report of the Director of Emergency Conservation Work, in fiscal year 1937 a total of 40 CCC camps operated in Georgia, distributed as follows:

National Forest camps: 9

Private Forest camps: 10

Soil Conservation camps: 9

National Monument camps: 2

State Park camps: 6

Military Reservation camps: 4

In fiscal year 1939 the

Annual Report of the Director of the Civilian Conservation Corps reports that a total of just 27 CCC camps operated in Georgia, distributed as follows:

National Park camps: 3

State Park camps: 4

National Forest camps: 5

Private Forest camps: 5

Biological Survey camps: 1

Soil Conservation camps: 9

(It’s interesting to note that between 1937 and 1939 the title of the annual report changed to reflect the program’s change from being called Emergency Conservation Work to Civilian Conservation Corps.)

As for enrollment, the

Annual Reports also list enrollment totals for 1937 and 1939 that provide a snapshot look at CCC enrollment in Georgia. Georgia’s monthly enrollment totals for fiscal year 1937 stack up like this:

July 1936: 12,299

August 1936: 11,605

September 1936: 9,941

October 1936: 12,350

November 1936: 11,706

December 1936: 11,150

January 1937: 12,125

February 1937: 11,675

March 1937: 9,752

April 1937: 10, 593

May 1937: 10, 182

June 1937: 9, 503

The

Annual Report for fiscal year 1939 shows a noticeable drop in monthly enrollment in the state of Georgia:

July 1938: 9,250

August 1938: 8,906

September 1938: 8,013

October 1938: 9,179

November 1938: 8,942

December 1938: 8,540

January 1939: 9,060

February 1939: 8,773

March 1939: 5,684

April 1939: 8,949

May 1939: 8,693

June 1939: 7,958

The Georgia Department of Natural Resources has a terrific page that lists CCC-built structures in the State Parks that you can still enjoy today. Click

here to see the list.

There is a short paper on the history of the CCC in Georgia posted at the website of the Civilian Conservation Corps Legacy. Written by Betty van Dongeren in 2007, the paper seems to deal more with the overall history of the CCC with a few references to work in Georgia, but it includes a list of sources and some photos. You can view the paper as a pdf document

here.Racism in the CCC was not a problem solely in the southern United States, however in the South where Jim Crow laws held sway for decades even after the end of the CCC, the issue of race in the CCC is particularly powerful. John Salmond’s seminal work on the CCC, an online copy of which you can read

here, includes a chapter titled “The Selection of Negroes.” Salmond makes particular reference to Georgia in the third paragraph of this chapter, writing: “Scarcely had selection [of CCC enrollees] begun, however, when reports from the South indicated that in that desperately poor region local selection agents were deliberately excluding Negroes from all CCC activities. Particularly deplorable were events in Georgia, which had a Negro population of 1,071,125 in 1930, or 36 per cent of the total state population. On May 2, 1933, an Atlanta resident, W.H. Harris, protested to the secretary of labor that in Clarke County, Georgia, with a 60 per cent Negro population, no non-whites had yet been selected for CCC work. Persons, director of CCC selection, immediately demanded an explanation from the Georgia state director of selection, John de la Perriere. The Georgia director blandly replied that all applications for CCC enrolment in Clarke County were “classed A, B and C. All colored applications fell into the classes B and C. The A class being the most needy, the selections were made from same.”

Despite further complaints from local groups, like the Atlanta branch of the National Urban League, officials in Washington preferred to remain outside the fray, with the hope that the situation would adjust itself, “without any apparent intervention from Washington.” But as it turned out, such a hands-off approach was not going to work over the long run and Director of CCC Selection Persons again followed up with the director of CCC selections in Georgia (John de la Perriere), this time by telephone. De la Perriere ultimately admitted that blacks were not being selected but denied it was on account of racism but rather, de la Perriere said that, “at this time of the farming period in the State, it is vitally important that negroes remain in the counties for chopping cotton and for planting other produce.” Persons knew better simply by looking at Georgia’s population statistics compared to enrollment of blacks in the CCC. Eventually it took a call to the governor of Georgia and a threat to withhold Georgia’s entire CCC enrollment quota to improve the situation; although one could easily argue that the issue of black CCC enrollment in the South was never fully resolved given that blacks were never represented in the CCC in numbers equal to their percentage of the population.

Ultimately, the experience of black enrollees in Georgia and nationwide, must be viewed through the prism of history and judged today as a series of small success that came about despite an overarching attitude of prejudice at the time. While the documentation records scores of vile episodes where blacks were denied the same opportunities in the CCC as their white counterparts, the record also reflects that local communities, in Georgia and nationwide, frequently embraced the all-black CCC companies that moved into their neighborhoods and often fought to keep them. For a longer, more detailed discussion of the African-American experience in the CCC, see the recent post over at

Forest Army.Larry N. Sypolt’s book

Civilian Conservation Corps: A Selectively Annotated Bibliography includes a number of listings for material dealing with the work of the CCC in Georgia, including the following items:

“The New Deal and Georgia’s Black Youth,” by Michael S. Holmes in the

Journal of Southern History 38 (August 1972), pages 443-460.

“The Civilian Conservation Corps and the State Park: An Approach to the Management of the Designed Historic Landscape Resources at Franklin D Roosevelt State Park, Pine Mountain Georgia,” a 1992 University of Georgia Master’s thesis by Lucy Ann Lawliss.

Mountaineers and Rangers: A History of the Federal Forest Management in the Southern Appalachians, 1900-81, by Shelley Smith Mastran, published by the U.S. Department of Agriculture Forest Service, Washington, DC, 1971.

NAACP Legal File: Cases Supported, CCC Boys, 1938-1939, National Association for the Advancement of Colored People, Frederick, MD, University Publications of America, 1988. This particular resource deals with the NAACP’s involvement in the cases of three Black CCC enrollees charged with murder in Georgia.

To view a collection of photos related to the work of the CCC in Georgia, visit

Vanishing Georgia, the Digital Library of Georgia. Once there, type in “Civilian Conservation Corps” in the search box and be amazed at what you find.

For an interesting page on Kennesaw Mountain National Battlefield Park and the location of its CCC camp remnants, visit

Waymarking.com. While you’re there, open the entire folder of waymarked CCC sites and you’ll marvel at the nearly 200 sites listed (to date). While we’re at it, here’s a link to the waymarking page for a CCC built bridge at

Indian Springs State Park, Georgia. This website is particularly interesting and useful if you’re looking for CCC work in your region or neighborhood.

The December 16, 1933 issue of

Happy Days reported the death of enrollee Alton Thrasher of Company 456, Robertstown, Georgia, in an automobile accident. The January 19, 1935 issue of

Happy Days reported the death of Bill Bruner of Company 1414. Bruner was reportedly killed in a diving accident.

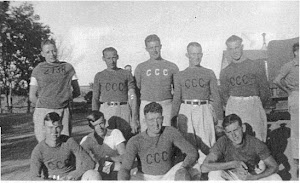

Sources: As with all the State-By-State posts, the map was taken from Stan Cohen's Tree Army. I highlighted the camp locations with colored dots for easier reference. The photo is of the Company 446 baseball team at camp D-92-G, Brunswick, Georgia and it also comes from the Cohen book. The Happy Days newspaper masthead was scanned from an original copy in my collection.

It’s amazing how the loose ends of research can sometimes tie together nicely and, perhaps not such a surprise when the loose ends don’t tie together so well. Then, there are those times when the loose ends come tantalizingly close to tying together nicely, but not quite.

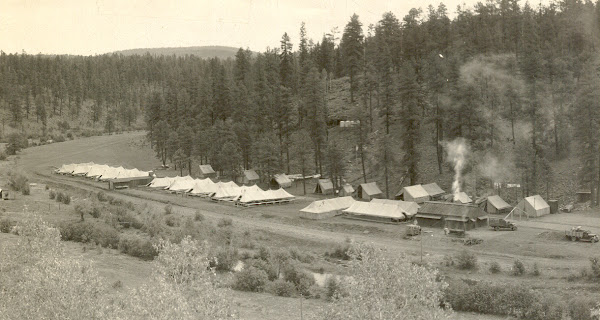

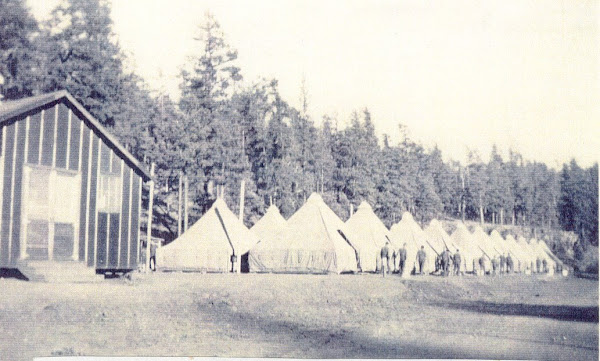

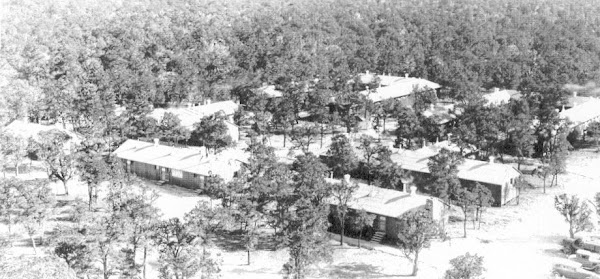

It’s amazing how the loose ends of research can sometimes tie together nicely and, perhaps not such a surprise when the loose ends don’t tie together so well. Then, there are those times when the loose ends come tantalizingly close to tying together nicely, but not quite. More recently, I happened to jump over to the James F. Justin Civilian Conservation Corps Museum and scrolled through the photo collection. While there I came upon a series of photos from Company 340, Camp DG-46-A near Kingman, Arizona. One in particular, of a civilian boss, "Cowboy" on a horse, caught my eye because it shows the front end of a pick-up truck with a clear view of the CCC license plate. My heart jumped! The terrain is nearly exactly the same as the terrain in my photo of a CCC foreman beside the pickup truck. Could it be the same truck? I couldn’t check the facts right away, but got around to it the very first chance I got.

More recently, I happened to jump over to the James F. Justin Civilian Conservation Corps Museum and scrolled through the photo collection. While there I came upon a series of photos from Company 340, Camp DG-46-A near Kingman, Arizona. One in particular, of a civilian boss, "Cowboy" on a horse, caught my eye because it shows the front end of a pick-up truck with a clear view of the CCC license plate. My heart jumped! The terrain is nearly exactly the same as the terrain in my photo of a CCC foreman beside the pickup truck. Could it be the same truck? I couldn’t check the facts right away, but got around to it the very first chance I got.