California, state number five in our state-by-state tour of the CCC, is another state that garnered a good deal of space in Perry Merrill’s book Roosevelt’s Forest Army, originally published in 1981. California had a lot of CCC camps. Merrill reports that in 1937 for example, there were 101 camps in California, divided as follows between the various technical services: 50 National Forest camps, 15 State Park camps, 11 National Park camps, 10 Private Forest camps, 9 Soil Conservation Service camps, 3 Division of Grazing camps, 1 Bureau of Reclamation camp and 1 Military Reservation camp.

California, state number five in our state-by-state tour of the CCC, is another state that garnered a good deal of space in Perry Merrill’s book Roosevelt’s Forest Army, originally published in 1981. California had a lot of CCC camps. Merrill reports that in 1937 for example, there were 101 camps in California, divided as follows between the various technical services: 50 National Forest camps, 15 State Park camps, 11 National Park camps, 10 Private Forest camps, 9 Soil Conservation Service camps, 3 Division of Grazing camps, 1 Bureau of Reclamation camp and 1 Military Reservation camp.In nearly a decade of work, the CCC accounted for some $25.6 million in allotments to dependents and for that money, enrollees built 306 lookout towers and houses, strung 8,704 miles of telephone wire, built over a million miles of truck trails and minor roads and performed tree and plant disease control on nearly 800,000 acres of land, among countless other projects. (Again, these figures are cited in detail in Merrill’s Roosevelt’s Forest Army.)

The 1937 Annual Report of the Director of Emergency Conservation Work reported the monthly enrollment numbers for California for fiscal year 1937 as follows:

August 1936: 9,048

September 1936: 7,961

October 1936: 8, 565

November 1936: 7,966

December 1936: 7,474

January 1937: 8,759

February 1937: 8,225

March 1937: 6,118

April 1937: 7,826

May 1937: 6,951

June 1937: 6,086

California is located in U.S. Forest Service Region 9 and the Forest Service’s history of the Civilian Conservation Corps includes an entire section devoted to work in California, which you can access here.

California is located in U.S. Forest Service Region 9 and the Forest Service’s history of the Civilian Conservation Corps includes an entire section devoted to work in California, which you can access here.Reportedly, the largest single undertaking by the CCC in California is the Ponderosa Way, an 800-mile long firebreak and truck trail cut through the Stanislas National Forest. The Forest Service history includes reference to this massive project:

In 2009 the Forest Service sponsored a Passport in Time project that put volunteers in the Ponderosa Way region with metal detectors to see what sorts of artifacts they could unearth. The results of the survey and recovery of artifacts might be characterized as a mixed bag. A brief write up by a USFS archaeologist, Stacy Lundgren states in part: “While some of the artifacts had little to do with the Ponderosa way and more to do with 1950s-era household trash, enough items were located to tell us we were on the right track. Historic maps and aerial photographs provided the clues to where to look and our volunteers provided the enthusiasm and dedication in the looking itself. This project was just the beginning in the planned documentation and interpretation of this significant resource.”

The history of fire suppression by the CCC is certainly nothing new and California had its share of fires to be fought, both forest fires and structure fires. I’m blessed in that I have corresponded with lots of former CCC enrollees over the years and one gentleman who’s been a font of information pertaining to CCC camps throughout California is Gordon Anderson. Gordie wrote to me some time back regarding a particular fire that occurred while he was assigned to the CCC camp at Big Basin, California. Here it is in his words:

While I was stationed in Big Basin, I was attached to the Forestry Fire Station in Felton, California just down the road – car fires, structure fires, and one forest fire – the Mountain Charlie Gulch Fire. That one was arson, started by an old guy riding a mule up the canyon and throwing lighted newspaper into the brush as he rode. He was spotted by a forestry plane, so when he rode out at the head end of the canyon, we were waiting for him. We took him back to the fire camp, gave him a drink, food, and a shovel and put him to work on the line – no rest, no relief. After two straight shifts of being booted onto his feet whenever he sat down, and full exposure to the fun of fighting fire, we turned him over to the sheriff, who wasn’t much more friendly than we were!

Gordie also recounted many humorous incidents that occurred during his time in the CCC in California. One incident involved an effort to establish a new pit latrine for the camp. Gordie wrote:

Dynamite figured in several of our little adventures – we used a lot of it. One of the messier ones: Our old privy had been there for several years and was plenty full, so the camp crew dug a new one just up the hill from the old one. The soil in those hills isn’t very absorbent, so the foreman handed a couple of the new boys a case of 40% and told them to load and shoot the hole to open it up for drainage, so they did and used the entire case! Unfortunately, they didn’t listen too closely to what he said and they loaded the wrong hole – the old one! When that blast when off it spread a thick layer of crap over the whole camp and believe me, it didn’t smell like no rose garden either! It still had a fairly strong perfume when we transferred out of there to Empire Meadows in Yosemite, several months later.

Gordie also commented on the impact the CCC experience had on him personally: I am sure that the experience in the CCC helped me a lot in later years; taught me how to obey orders (even if I thought they were stupid) and surely helped me to learn from my experiences. For instance, I learned not to sleep under a truck. On the Red Hill Fire, we were relieved, fed and I grabbed a blanket to get some rest. I flaked out under a truck and corked off and when I awoke, the truck was gone – never heard a thing. Fortunately, the Lord was with me that time. My brain certainly wasn’t!

The website of the Conference of California Historical Societies includes a brief nod to the work of the CCC.

The website of the Conference of California Historical Societies includes a brief nod to the work of the CCC.There’s a very nice series of web pages devoted to the work of the CCC in California, over at the California State Parks website. The site has multiple components and links to photos, brochures and other items of interest. There is also a list of featured state parks that includes La Purisima Mission, Big Basin Redwoods and Mount Diablo.

The true total number of enrollees killed while in the CCC may never be known. The CCC newspaper Happy Days reported some of the fatalities, but certainly not all of them. A current ongoing project of mine has been to gather data on CCC fatalities so I’ll close with a tidbit or two regarding CCC fatalities in California. One of the first CCC fatalities in California, as reported in Happy Days, was that of Cecil Loomis who was evidently killed when a CCC truck collided with an automobile. Cecil’s death was reported in the February 3rd edition of Happy Days. And it was just a couple months later that an enrollee by the name of Jones was crushed when the cement mixer he was helping move slipped off the truck, crushing young Jones to death

If you’d like to get some background on the purpose and scope of the State-By-State series, you can read the initial entry by clicking here.

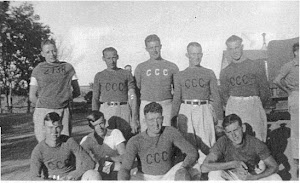

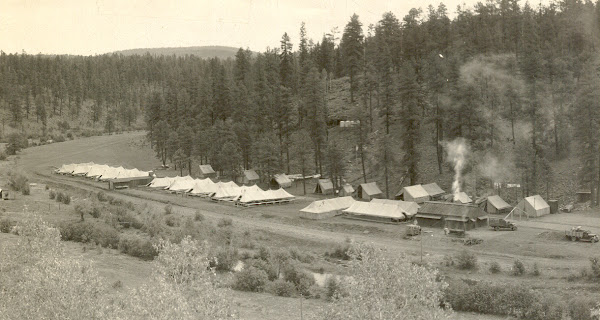

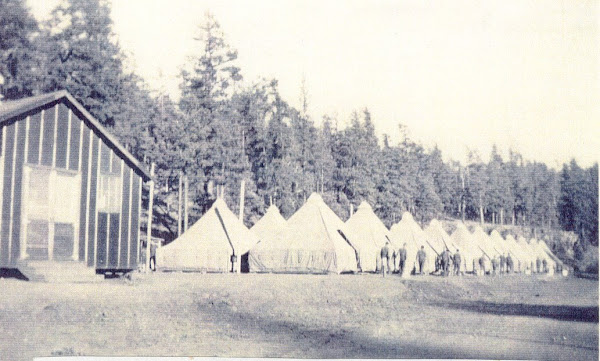

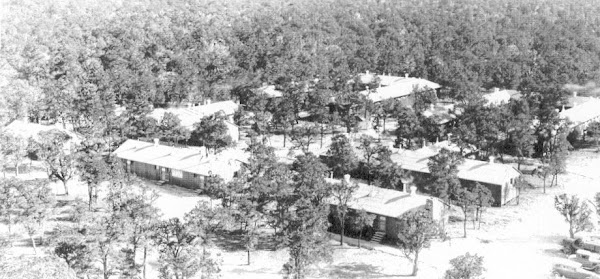

As with all the posts in the State-By-State series the camp location map was taken from Cohen's Tree Army and the camp locations highlighted. All photos are from the USFS and appear in Cohen's Tree Army except the image of the snow covered CCC camp, which is an image of the Big Basin CCC camp provided by Gordie Anderson.

The existing CCC documentation for the Alaska Territory seems nearly as remote as that largest of the 50 United States. Alaska had not yet entered the Union as a full-fledged state but was home to important CCC work nevertheless.

The existing CCC documentation for the Alaska Territory seems nearly as remote as that largest of the 50 United States. Alaska had not yet entered the Union as a full-fledged state but was home to important CCC work nevertheless.