Statistically, the most dangerous daily activity facing CCC enrollees was injury or death caused by vehicular accidents. Trucks transported enrollees to and from the work sites. Trucks often brought lunches and extra supplies to the work site during the day. Trucks carried enrollees into town on the weekend to take in a movie or to attend dances and trucks transported the enrollees back to camp when the fun was over. Trucks transported company equipment between camps and trucks moved enrollees from summer camps to winter camps when the weather got cold, often moving them back the other direction in the spring. No matter what the type of work being undertaken in the camp – forestry work, erosion control, construction of park improvements, or installation of irrigation systems – drivers were always the backbone of the effort.

.jpg) |

| An enrollee stands next to his battered truck. |

To be sure, in the first formative months of the program,

the CCC lacked a robust safety program, and by October 1933 it became clear the

organization had a safety problem. Director

Robert Fechner expressed dismay over the number of fatalities due to accidents

in the CCC, but despite his admonitions, the record did not improve and talk

turned to the creation of a formal safety program. Finally, in April 1934, with the strong

support of the War Department and the technical services like the Forest

Service and the National Park Service, a formal safety program was adopted. Under the program, CCC Safety Division

representatives visited each camp.

William Rutherford, a US Forest Service foreman working in a camp on

Colorado’s western slope, wrote home and mentioned that an inspector had

recently visited camp and was upset that enrollees were jumping out of the

backs of trucks before they’d come to a complete stop. At some point, Rutherford found himself

tasked with the job of managing the camp’s truck fleet, insuring the drivers

were properly trained and maintaining their vehicles. Safety committees were also established in

each camp and by the middle of 1936 the death rate for CCC enrollees had been

reduced to a point that was lower than that in the Regular army and lower for

young men in the same age group in the overall population of the United States.

Truck drivers were required to maintain their equipment and

expected to operate it in a safe manner.

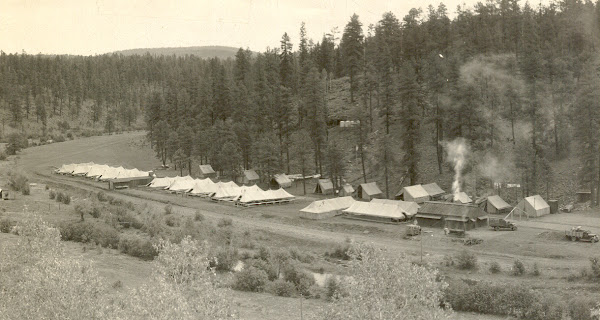

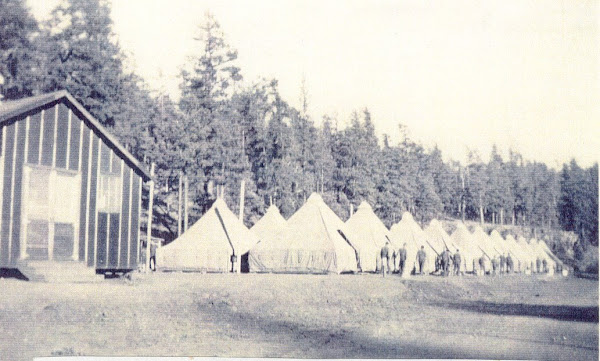

For example, in the camp at Vale, Oregon, Saturday’s were given over as

time for drivers to service and maintain their trucks, which they did, using a

large grease rack, built especially for the task. A driver’s safety record and driving ability

were documented and often referenced as part of their discharge paperwork; in

part as a means of showing prospective employers that a particular young man

had proven himself behind the wheel in the CCC.

|

| Grease rack, CCC camp Vale, Oregon, circa. 1940 |

|

| Merle Timblin (holding canteen) stands by his truck while a CCC work crew loads up. |

A truck driver’s code, issued to some drivers, including Merle Timblin, included the commitment to drive safely at all times and to strive diligently for a camp record of no lost time accidents.

To be sure, even with a strong safety program in the camps, accidents still happened and occasionally they were the result of misconduct on the part of one or more enrollees. In these cases, the camp commander would convene a review board to determine the cause of the accident and, if necessary, levy appropriate sanctions. Sadly, in the case of fatal accidents, the board would rule on whether the enrollee in question was at fault and whether the accident occurred in the performance of his regular duties.

|

| A newspaper reports the sad details of a fatal truck accident near Wallace, Idaho. |

The Death of Enrollee

Rocco Martello, Yellowstone National Park, 1939

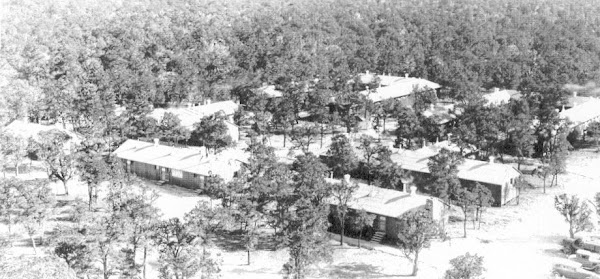

On October 3, 1939 a board of officers headed by Captain

Harley Jones, issued findings in the matter of the death of enrollee Rocco R. Martello,

who was a member of Company 3204 at the Nez Perce Camp YNP-5 near West

Yellowstone, Montana. Martello was a

passenger riding in the back of a stake bed Ford truck returning to camp

following an authorized recreation trip to West Yellowstone late on the night

of August 12, 1939. Approximately

sixteen miles into the journey and within the boundaries of Yellowstone

National Park, the driver was blinded by the lights of an oncoming vehicle. In his effort to avoid a collision, the

driver pulled the truck to the far right shoulder of the road, hitting a large

rock, resulting in his loss of control of the truck, which careened over an embankment,

rolling over in the process, coming to rest against some trees approximately 30

feet from the highway. Enrollee Martello,

seated on a bench seat in the rear of the truck was thrown from the truck and

pinned to the ground by two trees that were uprooted by the rolling truck, the

truck eventually coming to rest atop the uprooted trees and atop enrollee

Martello.

Captain Jones and the review board noted that enrollee

Martello died almost instantaneously.

Additionally, the board ruled that the death occurred in the performance

of duty and was not the result of Martello’s misconduct and that neither

alcohol nor drugs were a direct or proximate cause of the fatality.The board findings also include an affidavit from the driver of the truck, explaining the tragic details of the crash, noting that there were 23 enrollees in the rear of the truck and three, including the driver, riding in the cab. The driver goes on to attest that he received no instruction regarding the fact that three men should not ride in the cab of a CCC truck. Perhaps more tragic still, the driver admits to having had “about four beers” while in West Yellowstone that night, but goes on to claim that, “…there was no time in which I was not in full possession of my faculties. I was perfectly sober when I started do drive the truck back to camp.”

The documentation available does not record what action might have been taken against the driver and it would be unfair to speculate now, some 73 years later. It is enough to note that at least two lives were changed forever that night in Yellowstone National Park. Today the incident merely serves to remind us of the burden carried by truck drivers in the CCC.

|

| Motor pool, perhaps during vehicle inspection, CCC camp Vale, Oregon, 1940. |

Proceedings of B/O, Enrollee Rocco R. Martello Findings,

National Archives, Wash., DC.

Salmond, John A. The Civilian Conservation Corps,

1933-1942: A New Deal Case Study. Durham, NC:

Duke University Press, 1967.