August is a bastard.

Hot. Dry. Blazing.

Deadly. If you’re lucky, August

will break your will, steal what little hope you have left and leave you

dejected, hoping and praying for September or, better yet, October. If you’re unlucky, perhaps a bit too slow, a

bit too tired, a bit too inexperienced or careless, or wearing the wrong kind

of boots, that bastard August will kill you.

If you’re really unlucky, August will wipe out any vestige that you even

existed.

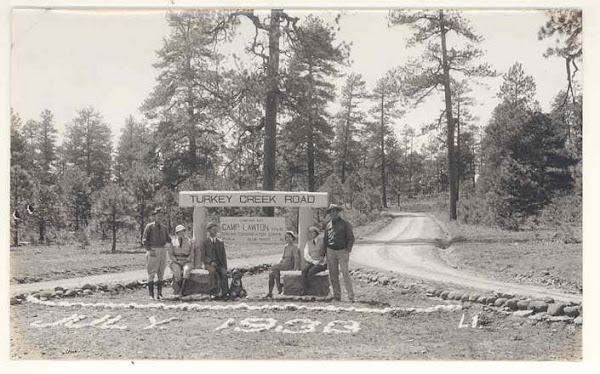

August 21, 2013 marks the 76th anniversary of the

blow up in Blackwater Creek, a fiery August conflagration that took the lives

of 15 firefighters, most of them young Civilian Conservation Corps enrollees

who battled wildfire on a rugged mountain slope hundreds of miles from their

Texas homes. I have posted more than one

article related to the events that occurred in the Shoshone National Forest

that blazing hot August afternoon and yet thoughts of that hot, smoky,

fire-filled afternoon always come back to me when this bastard month rolls

around and I begin to feel it’s too hot for my own good and then just as

quickly, I remember that it isn’t likely ever going to be too hot where I am,

compared to some panicky boys on a steep mountainside far from home in 1937.

Particularly heartbreaking is the fact that, while we know

very little about the men who died fighting the Blackwater Fire, we know virtually

nothing whatsoever of the CCC enrollees whose names filled the bulk of that

tragic headcount in 1937. Of the dead

men who were variously in charge of the fire suppression work at Blackwater we

know that one (Alfred G. Clayton) was born in Brooklyn, New York in 1892 and

that he was considered to be a ranger of the “old school” and that he was an

accomplished artist and writer. We know

that another (21-year-old Rex A. Hale) was originally from Afton, Wyoming, that

he worked his way of from CCC enrollee to a full-time Forest Service position

as Junior Assistant to Technician and that he left behind a wife and infant

daughter. We know that another of the

leaders who perished on the Blackwater Fire (Paul E. Tyrrell) was a graduate of

the University of California’s school of forestry, that he became a Junior

Forester in February 1937 and that he died as a result of burns he suffered

while trying to protect others during the fire.

Finally we know that one of those in charge of firefighting crews that

day at Blackwater Creek (James T. Saban) had struggled with personal demons

that had, in the past, forced him to leave work in forestry for a time and that

he had only been back working in the woods professionally for about 3 weeks

when the Blackwater blow up took his life.

Ranger Clayton and the men who were trapped in the gulch

probably didn’t have a good deal of time in which to consider their impending

fate. A mortally injured enrollee, Roy

Bevens, was found within 60 feet of Ranger Clayton, Foreman Saban, Junior Assistant

to Technician Hale and enrollees Gerdes, Griffith, Mayabb and Rogers. Bevens pointed out the location of the

fatality site in the gulch and reportedly expressed his thanks to God for

having survived, but he would later die from his burns.

As for the group of men with Ranger Post, the fire and the

terrain provided time to weigh options, to take action, to pray and to panic,

but there wasn’t evidently much time. In

the end, a rocky point was their last refuge as smoke enveloped them and flames

surrounded them on all sides. The group

shifted from one side of the clearing to another to avoid the heat and flames. Foremen and members of the technical services

struggled to keep order in the chaos and in some cases, literally fought with

the panicked men in order to keep them from bolting from the rocky clearing and

its scant prospects for safety from the inferno all around. Among the men trapped on the ridge with

Ranger Post that blazing, smoking fearful August afternoon were CCC enrollees

Earnest Seelke, Rubin Sherry, Clyde Allen and Herman Patzke. Seelke, Sherry, Allen and Patzke made a break

for it, along with Bureau of Public Roads employee Billy Lea. Only one would survive the effort.

The men were told to lie down, but according to Ranger

Post’s account after the tragedy, many insisted on sitting up or even standing

in order to say prayers. Ranger Post

noted later:

“Nearly all the boys grew panicky and instead of lying down

as instructed, a good many of them stood up and ran to the edge of the park,

turned and came back. Some of the boys

did not listen to any orders, instructions or cautioning and were insistent

upon standing up and saying their prayers.”

Foreman Paul Tyrrell restrained panicked enrollees at the

expense of his own safety; as he lay atop the panic stricken lads his body

created a shield that protected the boys from the heat. After the flames subsided, Foreman Paul

Tyrrell would be helped from the burn area only to succumb to pneumonia a few

days later.

For others trapped on what would later be named Post Point,

death came a bit more quickly, but only just a bit and certainly in no less a

traumatic fashion. Sam Van Arsdale, a

worker with the Bureau of Public Roads made a break for it at one point only to

retreat back into the clearing but not before seeing others make a similar less

successful break for safety. Van Arsdale

survived with burns but he recounted seeing other runners lie down in the

flames, seemingly resigned to their fate.

Van Arsdale later recounted his ordeal:

“I tried to get away from that terrible heat…I remember

there were other fellows running with me down the hill the first time. But they didn’t turn around. I guess they tried to run on through. I saw some of them just lay down in there and

let the fire burn over them.” (The Helena (Montana) Independent, August 24,

1937.)

In all likelihood, Sam Van Arsdale was witness to the death

of some who chose to make a break for it:

Bureau of Public Roads employee Billy Lea or CCC enrollees Earnest Seelke,

Rubin Sherry, Clyde Allen. History records

that only Herman Patzke survived his dash through the flames.

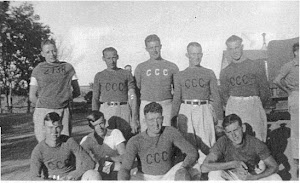

So here, for the first time that I am aware, are images of the four CCC enrollees who chose to make a run though the flames that blazing hot afternoon on a Wyoming mountainside 76 years ago. History seems to have forgotten them, but not quite.

|

| CCC enrollee Clyde Allen, killed at Blackwater Creek, Wyoming. |

|

| CCC enrollee Rubin Sherry, killed at Blackwater Creek, Wyoming |

|

| CCC enrollee Earnest Seelke, killed at Blackwater Creek, Wyoming. |