Maine was situated in the First Corps Area, and it is said

that Maine is the first point on the continental United States to receive

direct sunlight every morning when the sun rises above the eastern

horizon. Consequently, we can reasonably

argue that the CCC boys in Maine were the first CCC lads to see the sun every

day.

Perry Merrill reports on some basic CCC statistics for the

state of Maine in his book Roosevelt’s

Forest Army. Merrill quotes figures

from the 1937 Annual Report of the Director of the CCC, which I will expand

upon later in this post, but as a starting point, Merrill reported that an

average distribution of CCC camps in Maine for that period was:

State Forest:

1

Private Forests: 8

National Parks: 2

State Parks: 2

Military Reservation: 1

Merrill also refers to some overall figures for

the CCC in Maine; specifically that the aggregate number of Maine men who

gained employment in the CCC was 18,298 which included 16,686 junior and

veteran enrollees and 1,612 non-enrolled personnel. Overall, Merrill reports that the total

number of individuals who worked in Maine, regardless of their state of origin

was 20,434.

The 1937 Annual

Report includes a section of fold out spreadsheets broken down by state and

by project or job type. The list shows

that, among other things, CCC enrollees constructed 429 rods of guard rail in

Maine during fiscal year 1937. (A rod is

a surveying measurement that is equivalent to 16.5 feet so multiplying the 429

rods by 16.5 tells you that the CCC boys constructed quite a bit of guardrail

in Maine between 1936 and 1937 alone!)

Here are some other job type totals from the 1937 Annual Report that are not listed in Merrill:

Fire Suppression: 909 man days

Topographic Surveys: 819 acres

Signs, Markers and Monuments: 837

Emergency Work: 1,068 man days

The 1939 Annual

Report includes the same sort of fold out spreadsheets and a comparison of

similar job types finds these totals for fiscal year 1939 (year ended June 30,

1939:

Guard Rail: 6 rods

Tree Insect Pest Control: 3,849 acres

Fire Prevention:

0 man days

Fire Suppression:

4,723 man days

Topographic Surveys: Not Reported in the 1939

Report

Signs, Markers and Monuments: 55

Emergency Work: 27,783 man days

It is interesting to compare job totals from one

report to another and to speculate, for example, why the total length of guard

rail installed dropped so sharply between the 1937 and the 1939 annual

reports. It is also intriguing to see

that fire prevention work declined from 118 man days in the 1937 report to zero

days spent in fire prevention work in the 1938-1939 report. Perhaps not surprisingly, the amount of time

spent actually fighting fires jumped drastically from one report to the other

(909 man days in the 1937 report up to 4,723 man days in the 1939 report). Is it possible that the decline in fire

prevention work led to an increased need for firefighting in the year or two

that followed? It’s an interesting thing

to consider.

Year to year changes in CCC work rates for things

like fire suppression work might also be linked to major disasters that struck

the east coast during this period and nowhere is the effect of those disasters

more evident than in the comparison of CCC enrollee time spent on the job of

“emergency work” in 1936-37 compared to 1938-1939. The 1937 report lists 1,068 man days were

devoted to emergency work, whereas, in the 1938-1939 time period CCC enrollees

devoted 27,783 man days to emergency work.

The two disasters that likely account for such a drastic uptick in time

devoted to so-called “emergency work” were flooding and hurricane. Indeed, you could argue that one high water

mark for the CCC in Maine was their assistance in response to devastating

floods that struck in the winter of 1935-1936.

A personal recollection from enrollee Norman Wetherington, published in In the Public Interest, recounts the mobilization

of enrollees from Company 1124 in response to a call from the town of Bridgton:

“The afternoon of Friday the 13th, Lt. Fearer,

commanding officer of the 1124th company received a call for help

from the town of Bridgton. He drove down

to the edge of town to view the situation.

He took one look and went back to camp immediately. Inside of a half hour he had the entire camp

personnel loaded into trucks (seven forestry trucks and two Army trucks) headed

for Bridgton. The little army consisted

of two officers, all forestry supervisors, office personnel, and the entire

roster of CCC boys, except for three cooks that were left in camp to make

sandwiches”

Another natural disaster just two years later required the

mobilization of hundreds of CCC enrollees in response to the September 1938

hurricane, which impacted dozens of towns in western Maine. According to Schlenker, Wetherington and

Wilkins, writing in In the Public

Interest: The Civilian Conservation Corps in Maine, A Pictorial History, the

hurricane stuck with such force “that whole stands of forest growth were

wind-thrown, creating a high forest fire hazard.” Such was the fear of a forest conflagration,

the governor of Maine suspended hunting season in two counties and prohibiting

smoking or burning of any kind in the woods.

In addition to valuable fire reduction work, it is estimated that some

75,000,000 board feet of lumber was salvaged from the hurricane area.

To be sure, firefighting and disaster response were not the

only work efforts undertaken by the CCC in Maine. Among the premier Maine state parks to

benefit from the work of the CCC is Camden Hills State Park. Park visitors encounter the work of the CCC

almost immediately upon entering the park as they pass the stone entry gate and

contact station. Other CCC improvements

in the park include hiking and ski trails and a group pavilion. Ren and Helen Davis report that there are

more than 40 CCC-built structures in active use there, including a dining hall,

cabins, classrooms and bathhouses.

As we have seen in previous installments in the

State-By-State series, life and work in the CCC could be dangerous and enrollees

in Maine were not immune to that danger.

Happy Days, the official

newspaper of the CCC, reported on the deaths of at least two Maine

enrollees. Page one of the June 30, 1934

issue of Happy Days reported that

Charles A. Merrey of Company 154 at Bar Harbor, Maine had been killed in an

auto accident. The August 5, 1939

edition of Happy Days reported that

enrollee Clarence D Thurlow of Company 158 was killed when he fell from a cliff

while on leave.

For access to a terrific CCC-related page operated by the

Maine State Archives, click here. On this page you’ll be able to access a list

of Maine’s CCC camps and a Tribute page where personal stories of CCC service

are posted and honored.

|

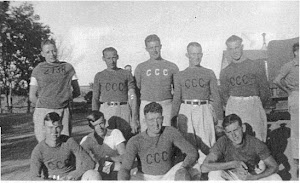

| Members of the Company 1130 baseball team, Camden, Maine, 1940 |

|

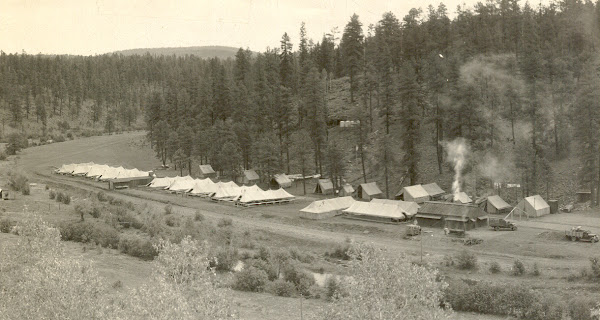

| Co. 1130, NP-3-Me, Camden, Maine |

|

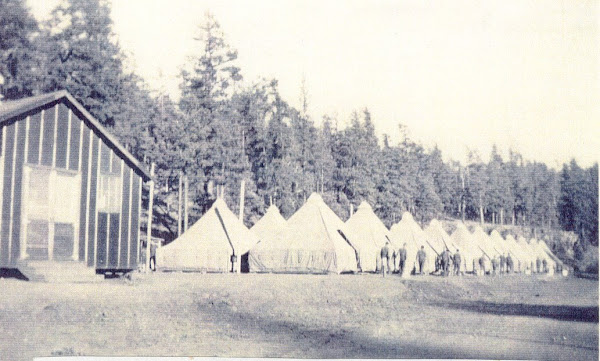

| Company 1130, NP-3-ME, Camden, Maine, 1940 |

| |

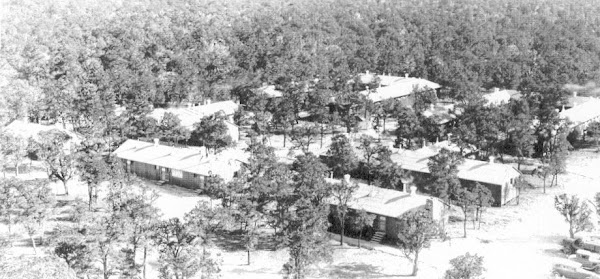

| First Corps area map, October 1940, from the Company 1130 Pictorial Review |

|

| Enrollee John McLeod works in the woodshop, Co. 1130, Camden, Maine |

Photos: With the exception of the first map, all images are courtesy of Mr. John McLeod, who served as an enrollee in Company 1130, camp NP-3-Me, Camden, Maine in 1940. John is a devoted advocate of the CCC legacy and an Iwo Jima Marine. Thank you, John!

Davis, Ren & Helen, (2011), Our Mark on This Land: A Guide to the Legacy of the Civilian

Conservation Corps in America’s Parks, The McDonald & Woodward

Publishing Company.

Merrill, Perry H, Roosevelt’s

Forest Army, 1981, Perry H. Merrill, Publisher.

U.S. Government Printing Office, Annual Report of the Director of Emergency Conservation Work, Fiscal

Year Ended June 30, 1937.

U.S. Government Printing Office, Annual Report of the Director of the Civilian Conservation Corps Fiscal

Year Ended June 30, 1939.

Schlenker, J.A., Wetherington, N.A. and Wilkins, A.H., (no

date), In the Public Interest: The

Civilian Conservation Corps in Maine, A Pictorial History, University of

Maine, Augusta.

Copyright, 2014, Michael I. Smith