Massachusetts was situated in the 1st Corps area,

which also included Maine, New Hampshire, Vermont, Rhode Island and

Connecticut. Some 50 or so parks and

forests in Massachusetts benefited from the work of the CCC and information on

most of those locations can be accessed on a website maintained by the State of

Massachusetts that you can access here. While there is not a great deal of detail

regarding specific projects, camp numbers or company numbers on this site, it

is admirable that the state government has taken the time and effort to list

where the CCC worked and to provide some information regarding what CCC-built

improvements you might encounter at a given location.

An online copy of the book The Civilian Conservation Corps, Shaping the Forests and Parks of

Massachusetts: A Statewide Survey of Civilian Conservation Corps Resources

(Jan. 1999) can be accessed here. The page is formatted to allow users to

search the text for specific words. For

example a search for the word “accident” will pull up the page that discusses a

monument dedicated to five enrollees killed in a truck accident at Sandisfield

State Park in December 1934, which we will revisit later in this article. This truly is a worthwhile resource for

anyone seeking information regarding the work of the CCC in Massachusetts.

Much has been made of the “wish list” of projects that the

state’s and technical services (Forest Service, National Park Service and the

Bureau of Reclamation, for example) had when the CCC was created in 1933. So many work projects and maintenance tasks

had gone undone for a number of years leading up to the Great Depression that

when Franklin Roosevelt created the CCC, agencies like the Forest Service had long

lists of projects that were, indeed “shovel ready” and in need of workers to

carry out the effort. Such was not

necessarily the case in Massachusetts, according to Perry H. Merrill, writing

in Roosevelt’s Forest Army: A History of

the Civilian Conservation Corps.

State leaders realized they would need to purchase acreage for parks and

forests if they hoped to keep Massachusetts enrollees working in their home

state. According to Merrill, some 50,585

acres of state lands were purchased for this reason between 1933 and 1939.

We have some enrollment and work statistics from 1937 and

1939 that shed light on the impact of the CCC in Massachusetts, which were

reported in the Annual Reports. For example, total monthly enrollment in

Massachusetts between July 1936 and June 1937 was as follows:

July 1936: 12,266

August 1936: 11,408

September 1936: 8,003

October 1936: 11,630

November 1936: 10,929

December 1936: 10,348

January 1937: 12,114

February 1937: 11,372

March 1937: 7,817

April 1937: 10,269

May 1937: 9,391

June 1937: 8,341

The distribution of CCC camps in Massachusetts in

fiscal year 1937 was as follows:

State Park Camps: 16

State Forest Camps: 17

Private Forest Camps: 4

Military Reservation Camps: 1

|

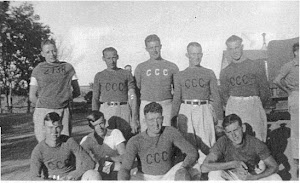

| US Forest Service photo, published in Stan Cohen's The Tree Army |

The annual reports include fold out charts that list

project totals for dozens of types of work broken down by state. Examples of specific work accomplished in

Massachusetts in fiscal year 1937:

Camp Stoves and Fireplaces: 142

Vehicle Bridges: 14

Topographic Surveys: 704.6

acres

Signs, Markers, Monuments: 1,735

Emergency Work, Search & Rescue: 733 man days

Emergency Work, “Other”: 21,101 man days

The Annual

Report for fiscal year 1939 reported total monthly enrollment in Massachusetts

between July 1938 and June 1939 as follows:

July 1938: 9,590

August 1938: 9,114

September 1938: 7,888

October 1938: 9,355

November 1938: 8,930

December 1938: 7,124

January 1939: 9,493

February 1939: 9,229

March 1939: 7,032

April 1939: 9,206

May 1939: 8,809

June 1939: 6,272

The 1939 Annual

Report includes more detail than the 1937 report. For example, the 1939 report gives totals for

selection of enrollees by state. So, in

fiscal year 1939 we know that 9,369 junior enrollees and 590 veterans were

enrolled from the state of Massachusetts.

The distribution of CCC camps in Massachusetts in

fiscal year 1939 was as follows:

State Park Camps: 9

State Forest Camps: 10

Private Forest Camps: 1

Examples of specific work accomplished in Massachusetts

in fiscal year 1939:

Camp Stoves and Fireplaces: 111

Vehicle Bridges: 4

Surveys: 2,711 man days

Signs, Markers, Monuments: 141

Emergency Work: 103,949

man days

It is always interesting to speculate regarding

why enrollment and work totals varied from year to year in the CCC. We know that as the economy improved,

enrollment in the CCC began to drop off because young men could more easily

find work. It also seems that CCC

enrollment was somewhat seasonal in some regions, with enrollment numbers

dropping off in agricultural areas during harvest season. Such may not have been the case with

Massachusetts but it is possible to speculate with some certainty regarding one

form of CCC work project: the category termed “emergency work.” We know that New England was hit by a

devastating hurricane on September 21, 1938 and, according to Aram Goudsouzian

in The Hurricane of 1938, 680 people

perished, 72 million feet of power lines were knocked down putting 88 percent

of the region in darkness and countless trees were uprooted. In the aftermath of the disaster Goudsouzian

reports, “Ten thousand workers from the Civilian Conservation Corps, which employed

young men in forestry and flood control programs, cleared streets and helped

save flood-threatened areas in Connecticut and Massachusetts.” In hindsight, it’s little surprise then that

the CCC focus on “emergency work” in Massachusetts jumped from around 21,000

man days in fiscal year 1937 to nearly 104,000 man days in fiscal year 1939,

the year the big hurricane struck.

(Remember that fiscal year

1939 included the period when the hurricane struck in 1938.)

Happy Days

was the official national newspaper of the Civilian Conservation Corps and it

included reports of camp activities in all of the 9 Corps areas. Sadly, some of the content of Happy Days was not so upbeat; accidents

and fatalities were commonly reported and no fewer than eleven Massachusetts

fatalities were reported in the pages of Happy

Days between 1933 and 1940.

According to the January 2, 1934 issue of Happy

Days, an enrollee in Company 1102 died from appendicitis. The aforementioned book The Civilian Conservation Corps, Shaping the Forests and Parks of

Massachusetts: A Statewide survey of Civilian Conservation Corps Resources notes

that Company 1102 was assigned to Camp

S-63, which was established at Otter River State Forest in 1934. Sadly, the microfilm copy of Happy Days is not clear enough to read

the enrollee’s name in this case but it appears to have been George –aki.

The most tragic episode in Massachusetts’ CCC

history was likely the death of five enrollees who were killed in a truck

accident on December 16, 1934 while en route to 8:00 AM mass at St. Peter’s

Church. The tragedy was reported on page

1 of the December 22, 1934 issue of Happy

Days. Killed in the truck accident

were enrollees Benoit Helie, James Leavy, Francis Kippenberger, Elden Holland

and Frank Capozzuto. Presumably, the

dead enrollees had been assigned to Camp S-71, in Company 196, based on

information in the aforementioned online resource, The Civilian Conservation Corps, Shaping the Forests and Parks of

Massachusetts. You can also read an

online article from 1997 about the area and the monument here.

Two years after the truck accident, Happy Days had the decidedly unhappy duty of reporting the death of Santino Boccabello of Company 1173, Salem, Massachusetts. According to the December 12, 1936 issue of Happy Days, enrollee Boccabello was killed in a landslide while working in a gravel pit. Ironically, the same issue of Happy Days contained an article reporting that the monthly fatal accidents were down by 31% in the CCC. No doubt the news came as cold comfort for Boccabello’s buddies in camp.

Four Massachusetts CCC fatalities are separated by

space and time but remain related by virtue of their commonality: in each case

the enrollee was struck by a car. The

death of enrollee Henry Piezarek, Company 135, Palmer, Massachusetts, was

reported in the July 2, 1938 issue of Happy

Days. Russell Crozier, assigned to

Company 1181, North Reading, Massachusetts was struck by a truck while on a

pass from camp, the report of his death appearing in the August 5, 1939 issue

of Happy Days. The front page of the

January 20, 1940 issue of Happy Days carried the sad news that enrollee Reed

Berry, from Company 4426, Lexington, Massachusetts, was struck and killed by a

car while on leave. Finally, Joseph

Budrunias, a veteran with Company 1181, was struck and killed by a car while on

leave; his death was reported on page 1 of the March 16, 1940 issue of Happy Days.

To be sure the primary purpose of Happy Days was to convey positive upbeat

stories about life and work in the CCC.

Any given issue might contain stories both earth shattering and obscure

from camps across the nation. The May

30, 1936 issue of Happy Days included

a number of brief articles detailing activities in Massachusetts camps,

including an account of an enrollee field trip to a local dam, a report that

Company 1139 at West Townsend, Massachusetts was preparing to reactivate their

camp radio station and news that Company 1189 was working on a poultry project.

To be sure the primary purpose of Happy Days was to convey positive upbeat

stories about life and work in the CCC.

Any given issue might contain stories both earth shattering and obscure

from camps across the nation. The May

30, 1936 issue of Happy Days included

a number of brief articles detailing activities in Massachusetts camps,

including an account of an enrollee field trip to a local dam, a report that

Company 1139 at West Townsend, Massachusetts was preparing to reactivate their

camp radio station and news that Company 1189 was working on a poultry project.

Elsewhere in the same issue is a brief story about

the work of a crew of enrollees in Company 1199 stationed at East Douglas,

Massachusetts. According to the report,

the crew accounted for the planting of 125,000 trees in the span of just 700

man-days. Put in perspective, one 6-man

detail from this crew planted 3,600 trees in a single day! The article goes on to detail some of the

recreational activities taking place in the camp after work ours.

In another article in the same column of print,

the May 30, 1936 issue of Happy Days reported that enrollees in Company 143 at

North Adams, Massachusetts had created a model club with 12 men working

individually on model airplanes as working as a group on a large plane model to

be displayed in the camp recreation hall.

Berg, Shary Page, The Civilian Conservation Corps, Shaping the Forests and Parks of

Massachusetts: A Statewide Survey of Civilian Conservation Corps Resources,

January, 1999, Landscape Preservation Planning and Design, Cambridge, MA. (Accessible online here.)

Happy Days,

May 30, 1936.

Merrill, Perry H, Roosevelt’s Forest Army, 1981,

Perry H. Merrill, Publisher.

U.S. Government Printing Office, Annual Report of the Director of Emergency

Conservation Work, Fiscal Year Ended June 30, 1937.

U.S. Government Printing Office, Annual Report of the Director of the

Civilian Conservation Corps Fiscal Year Ended June 30, 1939.

Copyright, 2014, Michael I. Smith